Thangka: Tibetan Buddhist Art Painting

Thangka is a unique form of painting art in Tibetan culture. It has distinctive ethnic characteristics, strong religious connotations, and a unique artistic style, using bright colors to depict the sacred world of Buddhism. This article will provide readers with a detailed explanation of Tibetan thangka. We hope that you will find it helpful after reading it.

What is a thangka?

Thangka (Tibetan: ཐང་ཀ་) is a form of painting on cotton or silk. Thangka is a distinctive form of painting art in Tibetan culture, with themes covering various aspects of Tibetan history, politics, culture, and social life. Thangkas are typically created using natural materials such as malachite, gold, silver, pearls, and cinnabar, and are hand-painted. Even after a century, thangkas remain vibrant and do not fade.

While many people today are drawn to thangkas for their unique patterns, for Tibetans, thangkas are not merely works of art; they are often used for meditation and prayer.

The Origins of Thangka

Thangka originated over 1,300 years ago during the Tibetan Empire (7th–9th centuries), when Buddhism was first introduced to Tibet. Since most Tibetans were illiterate at the time, high monks used mineral powders (such as lapis lazuli for blue and cinnabar for red) to paint images of the Buddha and scriptures on hemp cloth, thereby conveying Buddhist culture to the Tibetan people.

Later, Tibetan Buddhism branched into various schools, such as the Nyingma, Kagyu, and Gelug schools, and Thangka styles evolved accordingly, featuring different color palettes and patterns.

During the Ming and Qing dynasties (14th–20th centuries), artists began using gold leaf, silk, agate, and pearls to create thangkas, which were considered precious materials at the time. Sometimes, a complex thangka could take several years to complete.

The Role and Uses of Thangkas

Thangkas are extremely important to the Tibetan people. They are used during meditation, prayer, weddings, funerals, and other important ceremonies, and are an integral part of Tibetan life.

Different types of thangkas represent different blessings. For example, many people choose the Green Tara thangka (symbolizing “peace”) to hang in the living room, and the Manjushri thangka (symbolizing “wisdom”) to hang in children’s rooms.

This is also why many non-Tibetans now appreciate thangkas. People believe that wearing thangkas can bring them peace and good fortune.

The Artistic Styles of Thangka

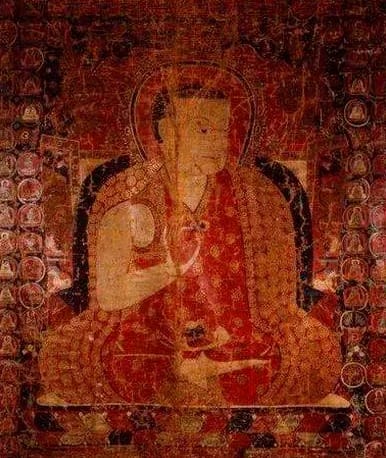

1.The Nepalese School

Thangka art was initially influenced by Nepalese styles. Around the 7th century, with the widespread introduction of Buddhism, there was a boom in the construction of temples and monasteries within Tibet. At that time, the murals and sculptures within the temples were created by painters and sculptors from Nepal and China. From then until the 15th century, works created by Nepalese and Tibetan artists were collectively referred to as the Nepalese School of Painting.

The Nepalese school of painting was most popular between the 11th and 13th centuries. Songtsen Gampo married Princess Chizun of Nepal, and Nepalese artists accompanied the princess to Tibet. They incorporated Nepalese artistic styles into local Tibetan art, forming the Nepalese school of thangka painting. This style is characterized by warm color tones, with the central deity occupying a prominent position in the center of the composition. The protective deities are arranged in neat small squares around the edges. The figures are relatively simple in design, with stiff postures, minimal and thin clothing, and heavy-looking ornaments.

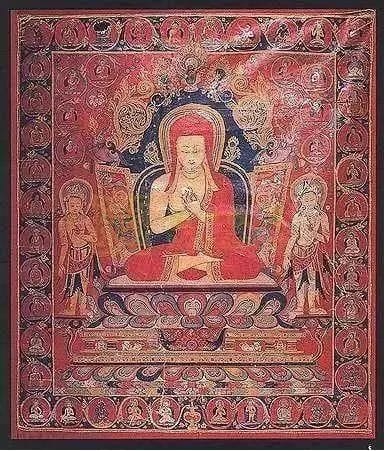

2.The Qi Gang School of Painting

The Qi Gang School of Painting was founded by Yadu Qi Wugangba. This school was mainly popular in the Ü-Tsang region during the 13th century. On the one hand, it inherited the artistic spirit of the Tibetan period and the period of division, and on the other hand, it absorbed some characteristics of the Nepalese painting style, mainly in terms of composition, which both inherited the composition of the Nepalese school and made slight changes. The central main deity occupies a relatively smaller space, and the color palette remains predominantly warm tones. In terms of background decoration, this school favors scroll patterns, and it depicts the details of the figures’ fingers, toes, and other subtle features with greater vividness and precision. This also renders the figures’ postures and attire more fluid and ethereal.

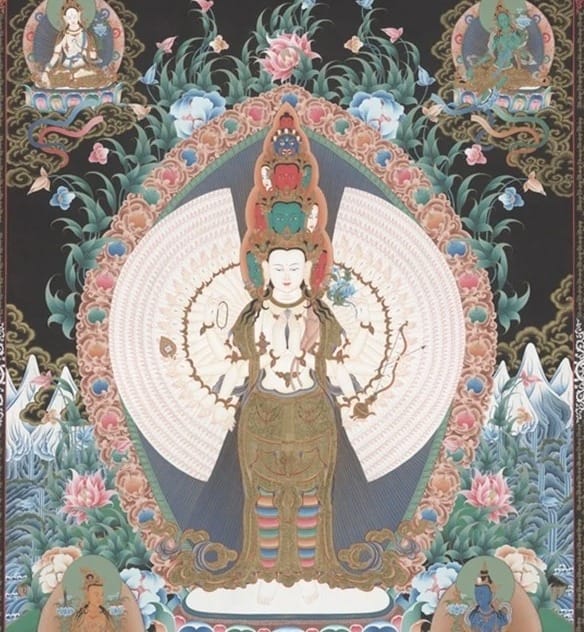

3.The Mian Tang School of Painting

The Mian Tang School of Painting (also known as the Men Chi School or Mian Tang School) originated and developed during the Zhanpu era, flourishing from the mid-Pazhu era to the Ganden Phodrang era. The founder of the school was Mianla Dondrup Gyaltsen, whose extant work, *The Measurements of Sacred Images*, provides a detailed discussion of the measurements used in painting and sculpture, points out errors in certain texts regarding these measurements and their detrimental consequences, and explains the practical methods of Tibetan painting. Drawing on various strengths, this school’s sculptural standards are rigorous. Compared to traditional block-like representations, it places particular emphasis on the use of lines, which are neat and flowing, with vibrant and bright color tones and rich variations. The painting style of the old Mian Tang school inherited the Indian-Nepalese painting style, but added local-style landscapes and floral patterns in the background treatment. The lines are balanced and precise, with light colors and gold lines for outlining.

From the late 17th century to the early 18th century, the Men-Tong school of painting reached its peak, producing a succession of outstanding artists. Many of the murals and thangkas preserved in the Potala Palace, Norbulingka, Drepung Monastery, Sera Monastery, and Ganden Monastery were painted by artists of the Men-Tong school. Tibetan painting reached maturity and prosperity with the emergence of the New Men-Tong school. Over several centuries of practice, Tibetan painters assimilated the early Indian-Nepalese style with the influence of Han Chinese Ming and Qing dynasty art, gradually forming the unique religious painting style of the Tibetan people. The period from 1949 to 1966 marked a turning point, and after 1966, the art form began to decline and fall into obscurity. Despite significant rescue efforts by local governments in the 1980s, the painting techniques remain in a precarious state.

4.The Qinze School of Painting

The Qinze School of Painting emerged in the mid-15th century and was primarily popular in the rear Tibet and Shannan regions. Its founder was Gongga Gangdui Qinze Qinmo (alternatively translated as Gongga Gangdui Qinze Chemu). Qinze Qinmo developed a passion for art from a young age. Building upon the traditional Tibetan-Nepalese painting style, he incorporated techniques from Central China, India, and other regions to establish the school. The Qinze School retained the Indian-Nepalese tradition of featuring a large central deity figure in its compositions, with the main subject prominently highlighted and surrounding smaller figures arranged in an orderly manner. However, in landscape depictions, it began to incorporate the expressive conventions of Han Chinese painting, gradually forming a distinct Tibetan painting language system.

It is said that the murals at Shannan Döji Dan Monastery were created by Qin Ze Qin Mo. In the art world, there has always been the saying that the Mian and Qin schools are “one literary, one martial.” The Mian school emphasizes “literature,” while the Qin school emphasizes “martial arts.” In comparison, the Qin school excels in depicting wrathful deities, whose faces are stern and imposing, with full-bodied and rounded figures. Their poses are steady yet dynamic, blending stillness with movement, and combining strength with grace, embodying a robust masculine beauty. Their color palette is rich and vibrant, skillfully employing contrasting hues that are bold and lively, with meticulous attention to detail in color coordination and a strong decorative flair. The Qinze School also excels in depicting mandalas, with unique styles, exquisitely detailed carvings, and intricate, luxurious patterns.

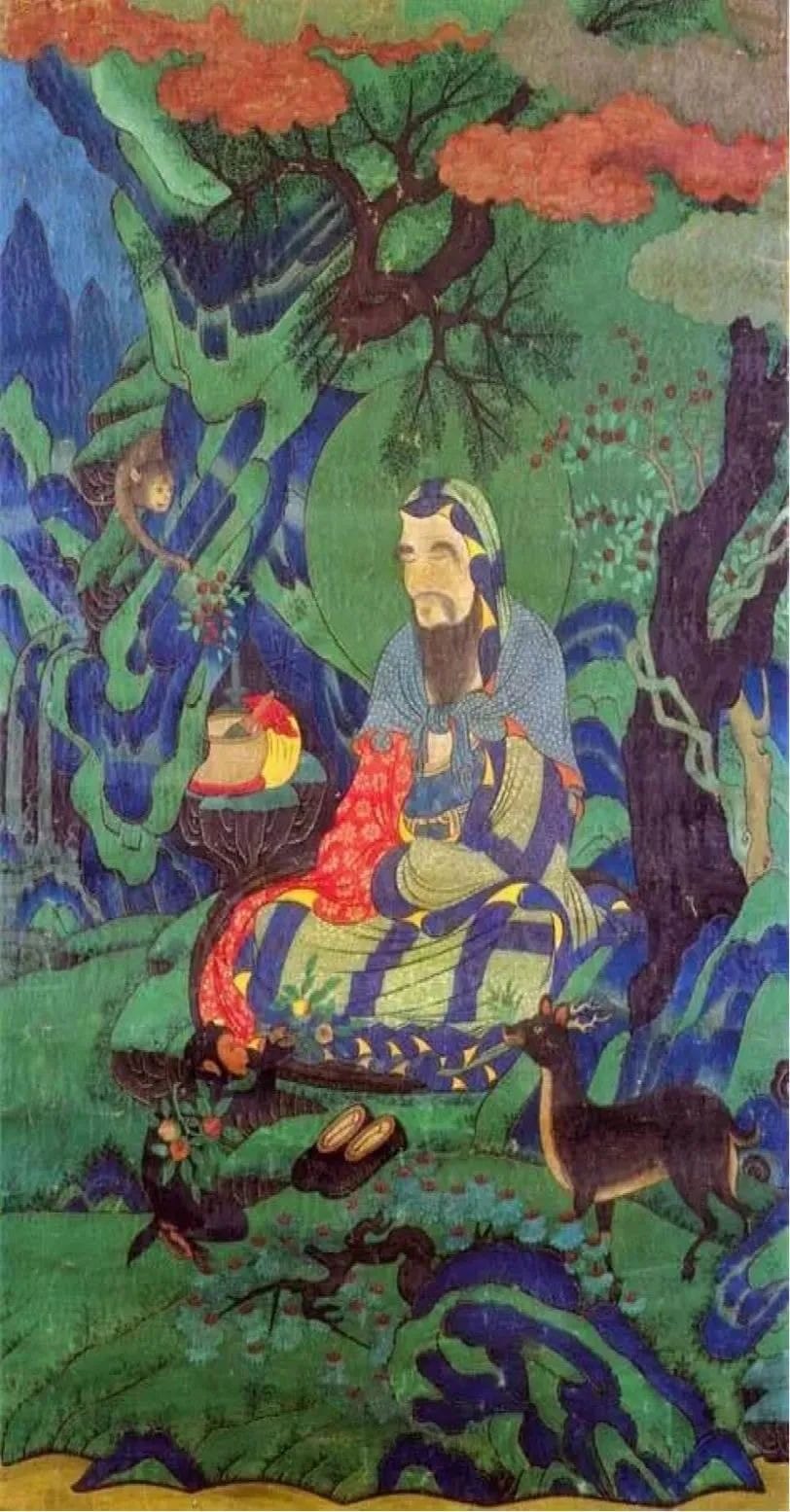

5.The Karma Garzé School

The Karma Garzé School, also known as the “Garma Garzé School,” is sometimes abbreviated as the “Garzé School” or “Garzé School.” It originated from the “Menzi” School. It is prevalent in the eastern Tibetan region, centered around Ganzi and Deqing in Sichuan Province and Changdu in Tibet. It is said to have been founded by the Namkha Tashi Rinpoche in the 16th century and named after the Gama Ba Grand Assembly.

The style of the Karma Garzé School has a complex origin. Its founder, the Nangkar Tashi Rinpoche, drew inspiration from South Asian Sanskrit-style copper Buddha statues and was deeply influenced by the painting style of the Maitreya School, particularly that of Gaden Shajampa Yejue Pende. Together with the 8th Karmapa Rinpoche, Mijiu Dorje, who lived during the same period as Namkha Tashi, he summarized the experiences of his predecessors and his own, compiling the “Linear Sun Mirror,” thereby establishing the theoretical foundation of the Gazi School. Later, the 10th Karmapa, Chöying Dorje, discovered the merits of Han Chinese architectural painting and blue-green landscape techniques in a set of Arhat silk thangkas, and began to paint thangkas using meticulous brushwork and vibrant colors. His works have a strong Han Chinese style, distinct from the Menri and Qinze schools of painting in the Ü-Tsang region. Following Namkha Tashi, two more painters inherited the Gazi School style: one was Chökyi Tashi, renowned for his blue-green color palette; the other was Gaxu Karma Tashi, celebrated for his innovative creations. Together with Namkha Tashi, they are collectively honored as the “Three Tashis of Gazi.”

Following “Gazi San Zaxi,” the miniature thangkas of Kangba Luhuo Langka Jie are truly unparalleled, while the painting plates left by Degé Pubo Zeren at the Degé Printing Institute have almost become the standard for the Karma Gazi school. The lineage of the Gazi school is very clear, with many famous artists emerging throughout the generations. Due to regional and teacher-disciple relationships within the school’s lineage, branches have emerged, leading to stylistic changes and the formation of the “Old Gazi School” and the “New Gazi School.”

6.The Xinmian School of Painting

The Xinmian School of Painting, also known as the Xinmian Tang School, refers to the Tibetan painters of the fifth Dalai Lama’s era (from the first year of the Ming Dynasty’s Taichang reign to the fourth year of the Qing Dynasty’s Kangxi reign). Quying Jiacuo, who inherited the essence of the Mian Tang School, integrated elements from the Karma Garzé School and the Qinze School, and absorbed certain aspects of Han Chinese painting. This marked the emergence of a new style, becoming the most distinctive feature of Tibetan ethnic painting—the “standard style,” which refers to the paradigm. It serves as the ‘classic’ and “model” of modern Tibetan Buddhist painting. To further consolidate the theocratic local government, the Gelug School extensively built monasteries in Tibet. To complete the task of constructing numerous monasteries in a short period, the new Mian School adopted the “Measurement Sutra” as the strict standard for creating murals and thangkas, gradually establishing the standard style of Buddhist painting.

Why are more and more people becoming interested in thangkas?

Nowadays, it is not only followers of Tibetan Buddhism who are interested in thangkas. Most people are attracted by the colors and craftsmanship of thangkas and regard them as works of art with spiritual power.

In today’s fast-paced environment, some people use the unique meaning of thangkas to relieve anxiety and pray for good luck and peace.

Regardless of the reason, after thousands of years of development among the Tibetan people, thangkas have become intertwined with people’s aspirations for goodness. This may be the most distinctive charm of thangkas.